Public safety providers in central Ohio had the chance to experience the future of broadband for managing emergency incidents.

Using a dedicated public safety 700 MHz LTE broadband network — FirstNet — constructed exclusively for this event, public safety personnel from fire, law enforcement, EMS, public safety telecommunications and other agencies came together to learn what a dedicated high-speed data will mean for public safety agencies in the United States.

The State of Ohio and Greene County, Ohio sponsored the event that was conducted in and around Beavercreek Township, a suburb of Dayton, Ohio. I spoke with Kelly Castle, project manager at OhioFirst.Net, to get her assessment of how the test was conducted and the feedback she received from the participants.

FireRescue1: Tell us about the test network set-up.

Castle: We had six months available to plan for this and it took us every bit of four months to get everything ready. We constructed a three-site, fully functional public safety LTE network in Greene County, Ohio. Our public safety network used the special Bandclass 14 (700 MHz) frequencies that have been set aside by the FCC for FirstNet’s use in the construction of the future nationwide public safety broadband network.

The test network, a prototype for what FirstNet will look like nationally, was completely separate from any of the commercial networks used by broadband carriers today. After we’d conducted all of our planned scenarios and tests, we decommissioned the network and returned all the frequencies we’d used for future FirstNet use.

How big was this prototype network?

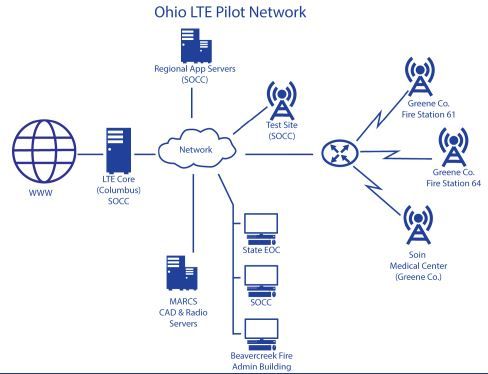

The network’s LTE core was located in Columbus, Ohio at the State of Ohio Computer Center with fiber-optic and microwave backhaul to three LTE sites in Beavercreek Township in Greene County, Ohio: Greene County Fire Stations 61 and 64 and Soin Medical Center. We also had two additional test sites at the SOCC and the State of Ohio Emergency Operations Center (See Figure 1).

OhioFirst.Net. Broadband Test, June 2016. Used with permission.

What scenarios did you have first-responders use to experience the system?

Experience is a good word. We wanted those first-responders in attendance to try out the new tools and see how they might make life easier for them as they provide service in the real world.

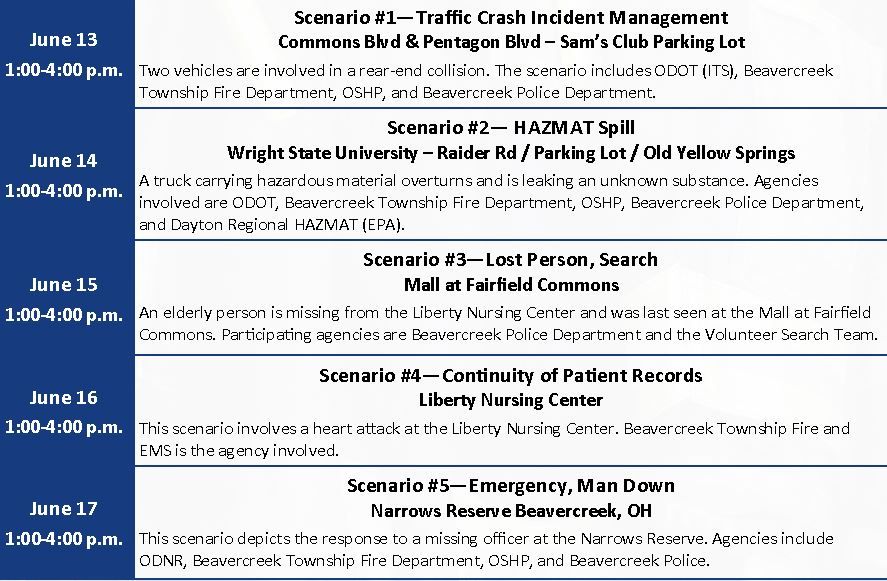

We developed five scenarios that would involve several public safety agencies and then conducted those scenarios at different physical locations (See Figure 2).

OhioFirst.Net. Broadband Test Scenarios, June 2016. Used with permission.

Were there any ah-ha moments?

There certainly was. Most of the participants were amazed at how much information could be shared between the responding public safety responders without a dispatcher in the middle. Now that’s not meant to minimize the contributions of those folks who work in our dispatch centers, but we all recognize that the dispatch center is a potential hang point where the sharing of information can be delayed, lost or subconsciously filtered.

What else had the participants talking?

Everyone was very impressed with the speed at which information appeared on their mobile devices and the clarity of photographs and video transmissions. It was like they were watching HD television.

Can you give us any examples?

On the final day, we conducted the “emergency man down” scenario involving an Ohio Department of Natural Resources officer who’d activated his man-down button on his radio.

With no other ODNR officer in area, dispatch checks map for the locations of any other first responders in area. The map shows the closest officers to be a Beavercreek policeman (LEX L10, APX portable, APX mobile) and the Beavercreek Fire Station 1. Dispatch also patched ODNR and Beavercreek radio talk groups together, then notified Beavercreek Police and Beavercreek Fire of the man down emergency, and the missing officer’s location was sent to the agencies’ LEX L10s and vehicles’ laptop computers.

The dispatcher responded to the man down activation by sending law enforcement and EMS to the officer’s location — as indicated by the STING app, a situational-awareness application.

Because the applications used to determine the downed officer’s location showed that he was approximately half mile away from his vehicle, back in the woods, EMS personnel responded with an ATV. The EMS crew aboard the ATV was able to provide streaming video of their response through the woods, which all the other responders could view in real time.

EMS found the ODNR officer unconscious with gunshot wound to his leg. At the same time, law enforcement officers that arrived at the ODNR officer’s vehicle in the parking lot noticed a white SUV parked nearby. They took pictures of the white SUV and its license plate using the Snapshot app, which they transmitted along with text back to dispatch.

Back in dispatch, they did a query on the plate and also checked the license plate recognition system to see if the vehicle had ever passed through the system.

With the time stamp from the ODNR officer’s body cam, along with the LPR info, the participants were able to review of video from a fixed-location camera in the area using software that filtered out all objects except for white vehicles. By doing so, they were able to quickly — in minutes — identify a white SUV that matched the photos and license plate number. All of that information was streamed to local and state law enforcement and the vehicle and suspect were quickly apprehended.

So you had a task that could have taken hours — manually reviewing available video feeds looking for the white SUV — being accomplished in minutes. You also had the video from the ODNR officer’s body cam that was a critical starting point for the whole process. And you had a variety of analysis applications being used to process and share information.

However, I sense a big “but” coming.

But, what really made it all possible was having the dedicated broadband network that could easily handle the huge amounts of data necessary to move those videos and images and text from the people who had the information to the people who needed it.

What did you and the participants find lacking?

Wireless phones still don’t have the same power of land mobile radios. Yes, they can handle the massive amounts of data being transmitted and received, but it really saps the battery.

Then there’s the issues with ambient noise when the user is outdoors, for example, wind and operating emergency vehicles and surrounding traffic. Those mobile devices are great when you’re in a car or indoors or in a command post situation, but not so much when you get outdoors.

In this exercise we used several different pieces of technology for transmitting and receiving information across the network. We used both Motorola APX mobile and portable radios, AT&T’s Sonim XP5 wireless phone, Motorola’s LEX L10 LTE portable radio, a commercial wireless phone and laptop computers.

Most of the participants were very impressed with the operation of newer portable radios that have been designed to work with broadband and WiFi. They also liked the functionality of the Sonim phone. There was a very distinct difference in the quality videos streamed to those newer radios and phone.

So, what’s next for OhioFirst.Net?

We’re continuing to testing and evaluating software and hardware using live events. Not long after the June scenarios, we deployed resources to the Red White & Boom Fireworks event on July 1. There were 400,000-plus people in attendance and we ran several scenarios including a missing child situation.

Now we all know that a missing child in that situation is a traumatic event for the parents, whether that child is missing 30 seconds, three minutes or three hours, right? Well, the first thing that the technology and dedicated broadband enabled us to do was identify the closest first responder to the location where the call for help originated. So that puts a police officer or firefighter or EMT in contact with the parents within minutes.

Then that first responder obtains a photograph of the missing child from the parents and streams it from their device, along with a description of the child, to every first responder on scene. So now you’ve got every first responder on scene looking for the same child at the same time.

We had the child in contact within four minutes. How cool is that?