| Editor’s note: The IAFF and the USFA released an updated version of its Voice Radio Communications Guide for the Fire Service in Oct. 2008. The guide focuses on seven sections of communications – basic radio communication technology, radios and radio systems, portable radio selection and use, trunked radio systems, system design and implementation, interoperability, and radio spectrum licensing and the federal communications commission. |

|

Purpose

The past few decades have seen major advancements in the communications industry. Portable communications devices have gone from being used mainly in public safety and business applications to a situation where they are in every home and in the hands of almost every American man, woman, and child. As users are added, there is more stress on the system; there is only so much room on the radio spectrum. The communications industry and the government have responded by making changes to the system that mandate additional efficiency.

These advancements have improved radio frequency spectrum efficiency, but also have added complexity to the expansion of existing systems and the design of new systems. Some of these advances in technology are mandated by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), while others are optional. The costs and operational effects of these changes are significant. Navigating through the complex technological and legal options of public safety communications today led to the development of this guide to assist the fire service in the decisionmaking process.

Why the Fire Service is Different

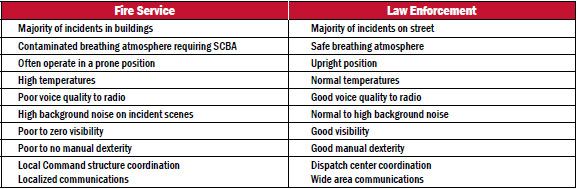

The life safety of both firefighters and citizens depends on reliable, functional communication tools that work in the harshest and most hostile of environments. Firefighters operate in extreme environments that are markedly different from those of any other radio users. Firefighters operate lying on the floor; in zero visibility, high heat, high moisture, and wearing self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) facepieces that distort the voice. They are challenged further by bulky safety equipment, particularly gloves, that eliminate the manual dexterity required to operate portable radio controls. Firefighters operate inside structures of varying sizes and construction types. The size and construction type of the building have a direct impact on the ability of a radio wave to penetrate the structure. All of these factors must be considered in order to communicate in a safe and effective manner on the fireground.

Radio system manufacturers have designed and developed radio systems that meet the needs of the majority of users in the marketplace. The fire service is a small part of the public safety communications market and an even smaller part of the overall communications market. This has resulted in one-size-fits-all public safety radio systems that do not always meet the needs of the fire service as a whole or those of a specific department. For a number of reasons, the fire service is unique among public safety and other municipal communications users. A large percentage of radio communications by most municipal or government users is done from vehicle-mounted mobile radios. Public safety radio users, law enforcement, and the fire service, use vehicle-mounted and portable radios. For much of the portable radio work by law enforcement personnel, the officer is outside on the street, in an upright position, with good visibility. The officer occasionally will go inside a building and communicate. This is in sharp contrast to the environments that firefighters face on a daily basis.

In many instances, radio systems perform better for law enforcement than for the fire service. The main reason for this is that law enforcement operates differently than the fire service. In the law enforcement operating model, the officers are in a deployed state outside patrolling the streets. When an incident occurs, the dispatch center notifies the patrol officers of an incident, and an officer or officers respond to the call. Once officers arrive onscene they may be operating as a single resource and only require communication with the dispatcher; at other times they may be operating with multiple responders, but the dispatcher remains the focal point of communications. Officers in these situations are wearing standard patrol attire and have good visibility.

The fire service operates in a staged state with resources located in fire stations. Calls are dispatched to specific units based on their location in relation to the incident. When more than one unit responds to an incident, an onscene Command structure is established to coordinate fire attack, provide safety and accountability, and manage resources. The units assigned to these incidents work for the local Incident Commander (IC), who is the focal point of communications on the fireground. The dispatch center assumes a support role and simultaneously documents specific fireground events, handles requests for additional resources, and may record fireground tactical radio traffic.

When comparing law enforcement to the fire service and other public safety some major differences are apparent.

|

NEXT SECTION - Basic radio communication technology

|

|