With the number of fires decreasing nationally and the difficulties in executing live burn training, it becomes important to ensure that our members are learning the most they can from our drills. It is not enough to just offer them experiences — we also need to show them how to learn from them. Research on experiential learning theory can help us with an educational process that improves learning.

In the fire service, we often think, “more is better.” Bigger trucks, bigger tools, more experiences are all “better.” Unfortunately as learners this just doesn’t work. As a matter of fact, too many experiences, especially extreme experiences such as those we can encounter in the fire service, can lead to “cognitive overload” and negatively impact learning. Think about it is as though your brain is “full.” The key is to allow our learners to have an experience and then be debriefed by an experienced facilitator for learning.

This debriefing is neither a critique nor what is commonly used in critical incident stress debriefing (CISD). A critique tends to have the goal of improving a process or identifying what went wrong rather than learning.

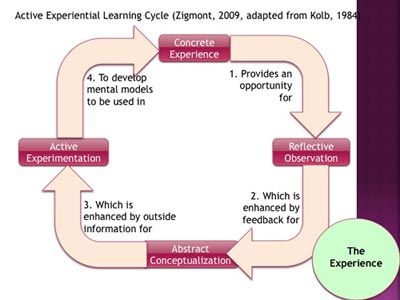

CISD helps with the emotional components of an experience, which is important, but is more about psychological safety than learning. In the context of learning, debriefing after a drill reflects moving the learner through the experiential learning cycle:

|

A drill, or real call for that matter, provides a “concrete experience,” which is an opportunity for learning. The experience itself is not where the learning occurs, but is the start of the cycle. Adults learn best from experiences that are challenging or extreme, which the fire service provides easily. The teaching does not occur in the experience itself as the learner is too wrapped up in actually doing the skills, fighting the fire or solving the problem.

After the experience, the learner must then go through a process of “reflective observation.” This is an opportunity for the learner to look back at the experience and determine what worked and what didn’t.

The challenge for the facilitator of learning is to make sure the reflective observation phase does not turn into a gripe session or critique. The facilitator can provide outside feedback on performance to help the learner analyze their experience. Additionally, it may be helpful to video record your drills to provide an objective look at the experience.

The next step is “abstract conceptualization.” The term may seem a bit funny, but the bottom line is that the learner needs to figure out a way to incorporate what they have learned into their “mental model” or decision-making process.

The process of integrating their new knowledge into their process is key in changing the way they react to future experiences. In other words, they have to make the learning “their own” to change practice.

In order to solidify this new way of thinking, the learners need to go through a period of “active experimentation.” This allows them to test out their new way of thinking and build it into their “muscle memory.” We often miss this step in our training due to logistical and time concerns, but then again that may be why what we have taught does not ‘stick’.

Facilitating learning through experience is a great way to improve practice but it takes time and effort. When it comes to saving lives, it is worth the time and effort. Get the most out of your limited training resources by working through the experiential learning cycle and debriefing after drills.